American Anti-Vivisection Society

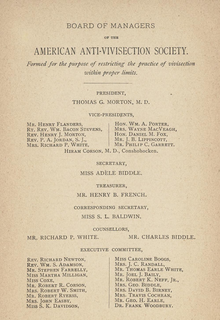

American Anti-Vivisection Society exhibit in 1909 | |

| Formation | 1883 |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | 801 Old York Road, Suite 204 Jenkintown, Pennsylvania, 19046 |

President | Sue A. Leary |

| Website | www |

The American Anti-Vivisection Society (AAVS) is a Jenkintown, Pennsylvania-based animal protectionism organization created with the goal of eliminating a number of different procedures done by medical and cosmetic groups in relation to animal cruelty in the United States. It seeks to help the betterment of animal life and human-animal interaction through legislation reform. It was the first anti-vivisection organization founded in the United States.[1]

History

[edit]

The American Anti-Vivisection Society was founded by Caroline Earle White in 1883 in Philadelphia.[2] The group was inspired by Britain's recently passed Cruelty to Animals Act 1876. Caroline White corresponded with Frances Power Cobbe, the woman who led the Victoria Street Society and had the Cruelty of Animals Act passed.[2] The Society advocated complete abolition of vivisection in scientific testing.[2] The first two members – Caroline Earle White and Mary Frances Lovell – worked with their husbands in the Pennsylvania Society to Prevent Cruelty to Animals (PSPCA), yet felt that their capabilities extended beyond what the PSPCA had to offer and, in 1869, founded the Women's Branch of the PSPCA (today known as the Women's Humane Society). The AAVS launched leaflet campaigns, held marches and recruited legislative advocates.[2]

The first American animal testing facilities were opened in the 1860s and 1870s, much to the dismay of animal rights pioneers. The biggest concern of the AAVS was the implementation of vivisection in medical testing.[2] Mark Twain's sketch "A Dog's Tale" was used by the Anti-Vivisection Society in its campaign against that practice. Additionally, it was issued by the British Anti-Vivisection Society as a pamphlet shortly after it was first published in Harper's Magazine in late 1903. In 1908, the AAVS tried to pass anti-vivisection legislation in Pennsylvania but was defeated by the "determination" of the medical profession.[2]

In the 1920s the AAVS sponsored a humane alternative to fur, a synthetic fur known as "humanifur".[3] The AAVS gained medical support but remained at odds with the American Medical Association (AMA), who argued that vivisection was critical to furthering medical advances. Anti-vivisectionists spent the next three decades trying to achieve legislation at state level but only succeeded on a national scale until the 1960s.[2]

In 1962, Owen B. Hunt president of the AAVS argued against regulation of vivisection and stated that the "American Anti-Vivisection Society stands, as it always has done, for abolition of vivisection on the ground that it is wrong, cruel and fruitless".[4]

The AAVS has consistently worked on educating the public on issues regarding animal cruelty as well as worked with the U.S. Federal government in passing legislations for animal rights.[5]

Publications

[edit]The organization's earliest publication was a magazine created in 1892 entitled the Journal of Zoöphily.[6] Mary Frances Lovell was its associate editor.[7] The Journal of Zoöphily informed its readers of recent vivisection and animal protectionism issues. The magazine published articles about animal intelligence, "hero dogs" and the loyal character of animals. It noted that animal cruelty was a sign of the decline of morality in society.[2] The publication changed its name a number of times, from The Starry Cross in 1922, The A-V in 1939, and resting finally with AV Magazine some years after that. Margaret M. Halvey secretary of the AAVS was managing editor of The A-V for 47 years.[8] The AAVS has had radio programs, such as "Have You a Dog?" as well as occasional spots and commercials on radio and television.[5]

Education

[edit]Animalearn was created in 1990 and is the AAVS' educational department.[9] The group intends to illustrate how science and biology can be taught in schools without actually using animals, like with dissection in the classroom. Animalearn conducts free workshops with educators nationwide to show how to teach science without the use of animals, as well as trying to incorporate animal-rights, in concept and practice, into the curriculum and educational environment of the school setting. The group has created what they call the Science Bank which is a program of "new and innovative life science software and educational products that enable educators and students to learn anatomy, physiology, and psychology lessons without harming animals, themselves, or the Earth."[10]

Presidents

[edit]| 1883–1884 | Henry Flanders |

| 1884–1887 | Thomas G. Morton |

| 1887–1891 | William R. D. Blackwood |

| 1891–1904 | Matthew D. Woods |

| 1904–1911 | Floyd W. Tomkins |

| 1911–1950 | Robert R. Logan |

| 1950–1978 | Owen B. Hunt |

| 1978–1990 | William A. Cave |

| 1990–present | Sue A. Leary |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Alethea Bowser. "The animal rights movement in America : Lawrence Finsen : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive". Retrieved 2020-01-30.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hausmann, Stephen R. (2017). "We Must Perform Experiments on Some Living Body: Antivivisection and American Medicine, 1850–1915". The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. 16 (3): 264–283. doi:10.1017/S1537781417000196. JSTOR 6347278.

- ^ Lederer, Susan E. (1997). Subjected to Science: Human Experimentation in America Before the Second World War. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0801857096

- ^ Humane Treatment of Animals Used in Research Hearings Before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce, House of Representatives, Eighty-seventh Congress, Second Session. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1962. p. 92.

- ^ a b Santoro, Lily. "History of the American Anti-Vivisection Society". Archived from the original on 2012-04-14. Retrieved 2008-11-25.

- ^ Journal of Zoöphily, HathiTrust.

- ^ Cherrington, Ernest Hurst (1928). "LOVELL, MARY FRANCES (WHITECHURCH).". Standard encyclopedia of the alcohol problem. Vol IV. Kansas-Newton. Westerville, Ohio: American Issue Publishing Co. pp. 1609–10. Retrieved 30 March 2024 – via Internet Archive.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Mrs. Halvey Dies: Author, Editor 92". Newspapers.com. 1946. Archived from the original on March 31, 2024.

- ^ "Humane Education". American Anti-Vivisection Society. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ "About Animalearn". Archived from the original on 2012-04-14. Retrieved 2008-11-25.

- ^ "The Birth of a Movement: The History of the American Anti-Vivisection Society". AV Magazine. 116 (2): 12–13. 2008.

Further reading

[edit]- "The Birth of a Movement: The History of the American Anti-Vivisection Society". AV Magazine. 116 (2): 2–15. 2008.

External links

[edit]- The American Anti-Vivisection Society - Official site

- American Anti-Vivisection Society - Online books